As I recall the milestones of my science fiction antiquity, I can’t help but thumb through the fragile pulp magazines of yore and reminisce about the blur of serials which were featured in early televisions. Those days strike me as far too quaint, like us depending on comic gumball machines, or onoughs for mindless distraction. The bald goofy chap, for instance, certainly had the weight of heroism thoughtfully rested on his shoulders. Flash Gordon, the very first sci fi hero to ‘beam’ into my living room a generation ago, had his ‘by-the-numbers’ adventures served as a prototype for TV in the 30s.

Flash Gordon, the hero of the 1930s, was catered to an audience seeking diversion from the dismal Great Depression, and purely for their entertainment. I remember seeing reruns of his exploits and how with nothing but his looks and charm, and rock-solid moral compass, he vanquished the terrible Ming the Merciless and other villains. He always had at his disposal dozens of tranquil moral victories. As a child, I was always ready to watch an emblematic hero defeat some emblematic evil. In retrospect, I think quite a lot of his fans were like me. They were not complex heroes and, no matter how fantastical their quests appeared, offered a soothing sense of realism in a moderately sized world where the good simply do not lose.

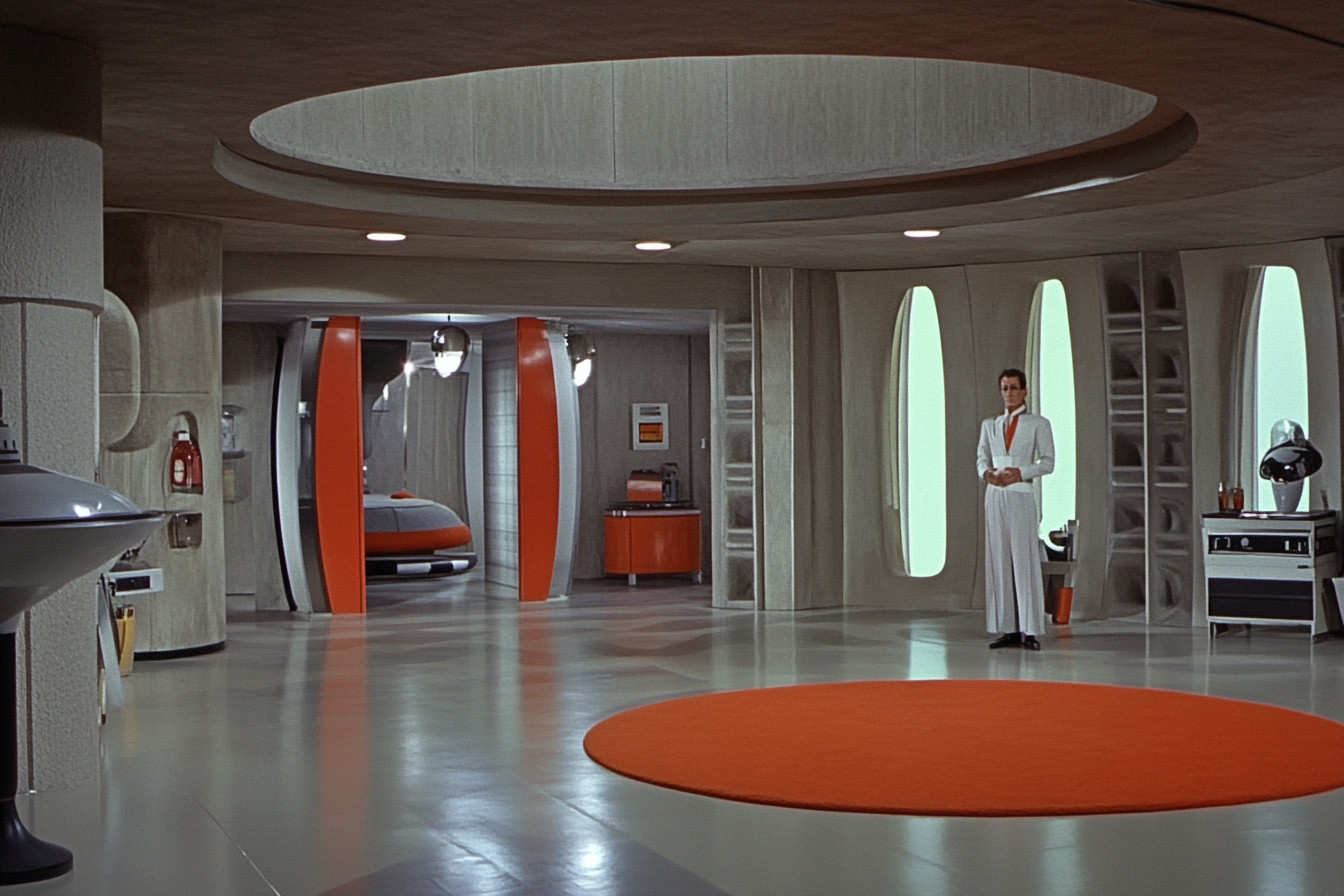

These heroes give us an unmistakable sense of the affinities, hopes, and dreams of the era. Characters like Gordon and Buck Rogers symbolized the mid-1900s striding optimism that ran rampant with the idea that humanity had the capabilities (or, at the very least, the potential) to conquer space travel. Flash Gordon and his likes believed it possible to cross frontiers with only a modest amount of intelligence needed. The models of spacecraft swung into camera view on concealed strings and other practical effects of their fillers added to their charm. Their charm was unmatched, but space exploration bore no consequences, rendering ‘Gordon’ as bubbles as classic Disney animations. Your living room transformed into an arena for a (mostly) wholesome romping illusion of hero worship brimming unrestrained. No care or worry loomed overhead whether or not the projector had been wrapped up.

Way over yonder in the distant future, eh? With the characteristics of society changing, the optimism beloved in Flash Gordon‘s world constructed a strange disharmony that centralized around fresh uncertainties society was now facing. This discord slowly gave rise to the cultural and technological focus uproar from the late 20th century. These factors, along with the shift from unambiguous endorsing heroes to morally struggling complex protagonists paved the way for the unbound surge of today’s literature.

The development shift from the golden era of sci-fi heroes like Flash Gordon to the more nuanced figures of later decades was not simply a matter of changing plots; it came from a civilization exploring its own depth and darkness. By the late 1970s and 1980s, the world was looking forward to a more dystopian and uncertain world. The previously optimistic view on humanity’s venture into outer space was at best muted – if not outright replaced – by Cold War fallout shelter discussions and even glimpses of those very shelters. And with that societal metamorphosis of the hero’s wife to a talk show hostess resided the Transformation of the stories and characters which combine science fiction with humanity’s darker elements.

A monumental milestone in this development was particularly marked by the premiere of Star Wars in 1977. I vividly recollect the first time I inserted a well-worn VHS of Star Wars: A New Hope into my VCR. The Imperial Star Destroyer, dominating the screen, coupled with the opening crawl nearly left me speechless. However, my imagination was captured by none other than Luke Skywalker. He truly felt like a hero—not someone who immediately had complete self-assuredness, but someone who fought with himself, his place in the galaxy, and grew into his role as a savior. There was no chance that he could have exuded confidence and swagger like “heroic” Flash Gordon.

In fact, I believe that the mistakes Luke made, together with the uncertainty posed by a conflict both within and outside, made his character much more endearing and inspiring.

The tale of Luke hits home because it illustrates a major shift in the perspective worldview. No longer was it simply good and evil. The first part of the “Star Wars” trilogy gave glimpses of clearer morality; “Star Wars”, through the lens of Luke’s journey, remained fundamentally about man’s condition. The handcrafted sets and physical models provided a far more diorama like assurance than the numerous computerized special effects in contemporary movies. Every single ordeal, every obstacle that Luke had to overcome was accompanied by a staggering and tangible authenticity that surrounded those moments in his journey where the meaning was overwhelming and extraordinary.

Simultaneously, a newwind was brewing with the emergence of a character that would transform the archetype of a sci-fi hero – Ellen Ripley from Alien. I recall attending a midnight screening of Alien in a run down cinema. Even during the time, the dilapidated theater and film presentation deck shared a sort of intimacy in its roughness. In the case of Ripley, she wasn’t a hero in the classical sense. Not of the aliens was she off because of some great strength or skill. In fact, she outlasted the situation because she happened to be a smart, ordinary working individual facing an extraordinary situation. She wasn’t even the central protagonist – a working-class woman straddling two realms was as close as the 70s and 80s can get to a sci-fi feminist utopia.

In any case, she pulled off making feminism a viable prospect for a genre where women were given the treatment of “your bodies, my canvas” and no real identity.

The most impressive trait of Ripley for me is how she single-handedly subverted the ‘hero’ stereotype in a genre that had been dominated by males – the ‘action’ genre. The gritty, lived-in universe of Alien was an astonishing difference from the space operas during the early periods of the century. In those stories, everything was polished to a perfect shine, presenting an outlandish vision of what life or travel into space would entail. Conversely, Alien was placed in a universe that seemed to reflect a more true-to-life, if not downright unappealing, vision of the consequences humanity would face while trying to inhabit space.

Indeed, this idea was so “realistic” that it spawned an entire sub-genre. The result? The space horror movie.

The image of a reluctant and flawed hero continues to develop into the 1980s. Take, for instance, Deckard in the 1982 film Blade Runner. He lacks empathy, and the movie itself asks at multiple moments what it means to be human. Experiencing it through a VHS player felt like visiting a drenched picturesque metropolis which, though beautiful, is painfully broken. Just as Deckard is a hero who is not a hero, a more than anything else weary, morally ambiguous, and always unfriendly to the heroic themes character who is trying to do what is right—supporting the system that defeats him.

During this period, the complexities and doubts of sci-fi heroes were signaling a metamorphosis in the narrative techniques employed within the genre. Heros like Luke, Ripley, and Deckard serve as reflections of a society struggling to accept that technology could lead to a bright, shiny future- especially given the fact that advancements in technology had already become a potential source for anxiety and dystopian outcomes. Such problems culminated in films like Alien and Blade Runner, in which the practicality of effects work compounded the anxiety of immersion within the worlds.

Even the most innovative characters seemed basic by today’s standards, yet Luke, Deckard, and Ripley ingrained the importance of showing vulnerability in the face of adversity. A message that remains relevant regardless of the evolving narratives framed by these worlds as we progress through time.

An additional transformation in the realm of science fiction occurred in the 1990s. Technology was no longer set in the distant future. It had cultivated during that period and became is a part of everyday life in the form of the internet, personal computers, and so on. Technology further increased the physical existence by filling it with the digital rather seamlessly. Each one of us were able to navigate through the “outer” space as well as “cyber” space due to our strongest hopes and deepest anxieties. Along with this global existence, a new icon emerged in our imagination was Neo, the hero of The Matrix (1999) which perfectly resonates with the fears and dreams of the century change.

I was pretty sure that The Matrix was special even before watching it because my expectations and viewing the film were extremely high. The film is one of those exceptional pieces which reach equilibrium between the visuals, storytelling, and the concepts underlying the story. First impressions alongside high expectations always set the pragmatics bar higher. So, upon our first encounter with Neo, “not-so Jedish” looking, immortal lead man Keanu Reeves, who in my eyes is the embodiment of the brand new sci-fi hero, bends backward in a slow-motion postcard-perfect rendition of bullet dodging.

What makes Neo so different is that he achieves victory on both physical and metaphysical levels. Neo doesn’t merely glance at the Matrix and the façade that it displays; he also perceives the “world” of 2000 machines. His success stems from the fact that he is an “awakened” being who can meaningfully claim the titles of “hero” and “chosen one” (in contrast to so many movie characters devoid of depth). The Matrix produced in 1999 attempts to offer a semblance of real transcendence within the framework of, “If you’re going to be a hero at least carry the values central to the stories told about heroes.”

Visually, The Matrix advanced the telling of science fiction stories, and what a story it is. The breathtaking views of the film propel the core idea of the story into a new realm of thought. Neo’s portrayal was rather dull, much like what most of us would be at first. When we encounter him at the beginning of the movie, he is living the life of a generic office zombie and gets axed for being late. His not-so-pleasurable work involves a lot of deskwork like the equally unpleasurable work done by the folks behind the 1995 flop, ‘Jean-y Mnemonic.’ It is the office life of a minimum-wage hamster wheel.

Neo’s character embodies a struggle that makes sense to everyone. Initially, he is sedated and programmed to be a mindless office worker. Eventually, he becomes self-aware.

In countless ways, Neo is the nuanced successor of those earlier, more straightforward sci-fi protagonists like Deckard or Ripley. While they grappled with the blurred lines of humanity versus the machine or the confidently unknown, Neo was up against a world where reality was up for skepticism. Even so, he was still a far cry from the stark and audacious certainty of Flash Gordon. The Matrix poses, for consideration, some very unthinkable to earlier sci-fi the simple optimistic queries. What if the world we perceive is nothing more than a façade? What if everything we so dearly hold onto is something that can easily be toggled on and off by a not so sincere, ostentatious remote control?

It seems that today’s sci-fi heroes are still drawing inspiration from Neo’s legacy. The Mandalorian character within the Star Wars universe embodies the Western antihero steeped in moral ambiguity yet incorporates themes of redemption and personal growth. Meanwhile, Rey from the latest Star Wars trilogy takes the search for self and belonging to a new level of contemporary women’s space opera.

In contrast to the iconic Luke Skywalker, who encapsulated a more straightforward ‘light side’ approach to the Force, Rey contends with far deeper male-female relations and a Force that is far more nuanced than just light and dark.

These modern-day heroes embark on a far deeper journey than the classic ‘hero’s journey.’ They navigate realms of self-exploration portraying a contemporary rendition of what a “hero” truly embodies. The term “hero” has lost its meaning and can now refer to anyone from a common citizen to an NFL quarterback. Our society has developed an unreasonable need to hand over that title to just about anyone. The kind of idol we are now told to admire is far more peculiar and intricate than those we previously idolized for their athletic and moral conduct outside the sporting arena.

Yet, despite the relentless progression of technology, a yearning still exists for the handiwork of human beings, for the authentic and the useful. This has become apparent to me in some latest sci-fi projects, including the revival of practical effects, such as sets and animatronics in The Mandalorian. It seems as though The Matrix and its laser digital wonders of ‘cube land’ are desperately seeking balance with the molded rubber charm of its ancestor. The essence of great sci-fi remains a hero a questioner of the status quo. What I gather from all these is that human storytelling tools may advance, but the tools will always need a SCiFi world vision which invites people to see a new perspective.

Hearing Neo speak, while contemplating the journey from Flash Gordon, leaves me in wonder over how each hero embodies the hopes and dreams of their era. In this case, I must acknowledge the incredible influence of penny dreadfuls, which financed more electrifying entertainments as science fiction became a notable power player in our culture. But the underlying motif is a far more concerning one: the story of us – how, despite everything, we have changed, questioned, and still managed to reach for the nature of the stars, even as the stars themselves have transformed.